A digital archive of

slave voyages details the largest forced migration in history

A digital archive of slave voyages details the largest forced migration in history

Philip Misevich, St. John's University; Daniel Domingues, University of

Missouri-Columbia; David Eltis, Emory University; Nafees M. Khan, Clemson

University , and Nicholas Radburn, University of Southern

California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

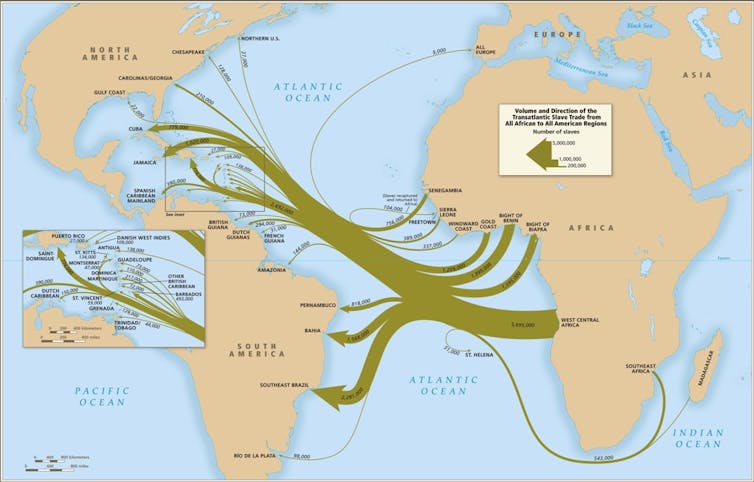

Between 1500 and 1866, slave traders forced 12.5 million Africans aboard transatlantic slave vessels. Before

1820, four enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic for every European, making

Africa the demographic wellspring for the repopulation of the Americas after

Columbus’ voyages. The slave trade pulled virtually every port that faced the Atlantic Ocean – from Copenhagen to

Cape Town and Boston to Buenos Aires – into its orbit.

To document this enormous trade – the largest forced

oceanic migration in human history – our team launched Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

Database, a freely available online resource that

lets visitors search through and analyze information on nearly 36,000 slave

voyages that occurred between 1514 and 1866.

Inspired

by the remarkable public response, we recently developed an animation feature

that helps bring into clearer focus the horrifying scale and duration of the

trade. The site also recently implemented a system for visitors to contribute

new data. In the last year alone we have added more than a thousand new voyages

and revised details on many others.

The

data have revolutionized scholarship on the slave trade and provided the

foundation for new insights into how enslaved people experienced and resisted

their captivity. They have also further underscored the distinctive

transatlantic connections that the trade fostered.

Records of unique slave voyages lie at the heart of the project. Clicking on individual voyages listed in the site opens their profiles, which comprise more than 70 distinct fields that collectively help tell that voyage’s story.

From

which port did the voyage begin? To which places in Africa did it go? How many

enslaved people perished during the Middle Passage? And where did those

enslaved Africans end the oceanic portion of their enslavement and begin their

lives as slaves in the Americas?

Working with complex data

Given

the size and complexity of the slave trade, combining the sources that document

slave ships’ activities into a single database has presented numerous

challenges. Records are written in numerous languages and maintained in

archives, libraries and private collections located in dozens of countries.

Many of these are developing nations that lack the financial resources to

invest in sustained systems of document preservation.

Even when they are relatively easy to access, documents on

slave voyages provide uneven information. Ship

logs comprehensively describe places of

travel and list the numbers of enslaved people purchased and the captain and

crew. By contrast, port-entry records in newspapers might merely produce the

name of the vessel and the number of captives who survived the Middle Passage.

These

varied sources can be hard to reconcile. The numbers of slaves loaded or

removed from a particular vessel might vary widely. Or perhaps a vessel carried

registration papers that aimed to mask its actual origins, especially after the

legal abolition of the trade in 1808.

Of course, not all slave voyages left surviving records.

Gaps will consequently remain in coverage, even if they continue to narrow.

Perhaps three out of every four slaving voyages are now documented in the

database. Aiming to account for missing data, a separate assessment tool enables users to gain a clear understanding of the

volume and structure of the slave trade and consider how it changed over time

and across space.

Engagement with Voyages site

While

gathering data on the slave trade is not new, using these data to compile

comprehensive databases for the public has become feasible only in the internet

age. Digital projects make it possible to reach a much larger audience with

more diverse interests. We often hear from teachers and students who use the

site in the classroom, from scholars whose research draws on material in the

database and from individuals who consult the project to better understand

their heritage.

Through a contribute function, site visitors can also submit new material on

transatlantic slave voyages and help us identify errors in the data.

The

real strength of the project – and of digital history more generally – is that

it encourages visitors to interact with sources and materials that they might

not otherwise be able to access. That turns users into historians, allowing

them to contextualize a single slave voyage or analyze local, national and

Atlantic-wide patterns. How did the survival rate among captives during the

Middle Passage change over time? What was the typical ratio of male to female

captives? How often did insurrections occur aboard slave ships? From which

African port did most enslaved people sent to, say, Virginia originate?

Scholars

have used Voyages to address these and many other questions and have in the

process transformed our understanding of just about every aspect of the slave

trade. We learned that shipboard revolts occurred most often among slaves who

came from regions in Africa that supplied comparatively few slaves. Ports

tended to send slave vessels to the same African regions in search of enslaved

people and dispatch them to familiar places for sale in the Americas. Indeed,

slave voyages followed a seasonal pattern that was conditioned at least in part

by agricultural cycles on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The slave trade was

both highly structured and carefully organized.

The website also continues to collect lesson plans that teachers have created for middle school, high

school and college students. In one exercise, students must create a memorial

to the captives who experienced the Middle Passage, using the site to inform

their thinking. One

recent college course situates students in

late 18th-century Britain, turning them into collaborators in the abolition

campaign who use Voyages to gather critical information on the slave trade’s

operations.

Voyages has also provided a model for other projects,

including a forthcoming

database that documents slave ships that

operated strictly within the Americas.

We also continue to work in parallel with the African Origins database.

The project invites users to identify the likely backgrounds of nearly 100,000

Africans liberated from slave vessels based on their indigenous names. By

combining those names with information from Voyages on liberated Africans’

ports of origin, the Origins website aims to better understand the homelands

from which enslaved people came.

Through

these endeavors, Voyages has become a digital memorial to the millions of

enslaved Africans forcibly pulled into the slave trade and, until recently,

nearly erased from the history of not only the trade itself, but also the

history of the Atlantic world.

Philip Misevich, Assistant Professor of

History, St. John's University; Daniel Domingues, Assistant Professor of

History, University of

Missouri-Columbia; David Eltis, Professor Emeritus of

History, Emory University; Nafees M. Khan, Lecturer in Social Studies

Education, Clemson

University , and Nicholas Radburn, Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Southern

California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original

article.